“The Joy Of Shedding Their Chains” – In Praise Of Pune One

10/02/2020 in The World

-

The media has often painted a luridly sensationalist, negative picture of ‘the world of Osho’, terming Sannyas “a cult”, the master “the sex guru”, and highlighting the psychotic excesses of Sheela & co. during the Ranch period. But here’s an instance where an eminent journalist, Bernard Levin, repors from an entirely different, positive perspective, having taken the trouble to spend time at the Pune ashram, interact with Osho’s people and join in some of the activities there.

That was nearly 40 years ago, halfway through Pune One….

By Bernard Levin, ‘The Times’ 10 April 1980

If it is true, and I cannot see how it could not be, that a tree must be known by its fruit, the followers — he calls them neo-sannyasin — of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh are in general an exceptionally fine crop, bearing witness to a tree of a choice, rare nature. The first quality a visitor to Rajneesh’s ashram notices — and he never ceases to notice it — is the ease and comfort with which they wear their faith. Though they are unshakably convinced (I met only one with any residual doubts) that Rajneesh has enabled them to find a meaning for their lives and for their place in the universe, there was no trace of fanaticism in them, and in most not even fervour.

A prominent British journalist would have been a considerable catch for them, and they were plainly aware of it, for the efficiency and thoroughness with which they met all my requests, answered all my questions and showed me all I wanted to see, made it quite clear that the administrative side of the enterprise is fully aware of the world outside and of the way it runs; whatever else these people are, they are not spiritual troglodytes. But if they would have been pleased to land me, there was never a glimpse of a net; the hours of talk were absolutely free of any proselytising. They have truly understood what Rajneesh meant by the words I quoted yesterday. ”If you go to Hell willingly, you will be happy there; if you are forced into Paradise you will hate it.”

The joy with which they are clearly filled is, as anyone who listens to Rajneesh must deduce it would be, directed outwards as well as in; I cannot put it better than in saying that they constantly extend, to each other and to strangers, the hands of love, though without the ego-filled demands of love as most of the world knows it. They have shed their chains, and they demonstrated their freedom easily and unobtrusively, though the results at first can be startling ; a young married couple I met spoke within ten minutes of a marital problem not usually discussed before strangers (or indeed at all), yet there was no exhibitionism or inverted vanity involved, only the innocent naturalness of the nakedness in Eden before the Fall.

They come not only from haunts of coot and hern, but from all over. I met an accountant, a journalist, a psychotherapist, a housewife, a farmer, a lecturer in Business Studies, among others. Few of them are pursuing their own professions in the ashram (the lecturer in Business Studies agreed cheerfully that there was not much call for such things chez Rajneesh) and those who live full-time on the premises or — for the place is very over-crowded — in Poona itself, are commonly assigned tasks which are themselves designed as part of the learning process, the point being that when an individual finds himself doing the floor- scrubbing with real joy, he is already a long way towards the goal.

Of course, everything that happens on the ashram is designed for the same purpose. The workshops are extensive and impressive; these are no fumbling amateurs messing about with batik and linocuts, but serious craftsmen turning out furniture, metalware, silver inlaying, screen-printing and the like, of high quality. But the point is that almost all of them started without any skill at these trades. The further point is that they are all obviously happy in their work, and the point beyond that is that they would obviously still be happy if they were there doing something else entirely; this is not a story of people who discover an unsuspected talent in themselves, but one of the searchers who find in themselves something of which all talents, indeed all activities whatsoever, are gleaming reflections.

The encouragement of this discovery is also the purpose of the therapy-groups and the various forms of ”dynamic meditation”. Liberation from the ego must start with liberation from the layers of self-consciousness in which we are wrapped, as in the ”Sufi- Dancing” (I don’t think Omar Khayyam would have noticed much of the Sufis’ teaching in it, mind you). This consisted of some simple (though not simply spontaneous) steps and movements, with constant change of partners and such exercises as pausing to look into the eyes of neighbours. I was dragged onto the floor by one of my new-found friends (”You don’t have to do anything!”) and even this limited experience of the disembarrassing process made me see its necessity and efficacy.

There is jargon, of course. An experience is ”heavy”; someone is ”into” this or that technique; asked what he had been before coming to the ashram, one young man replied, not ”a musician”, but ”I moved in music energy”. Clearly it had never occurred to any of the full-bearded, long-haired men that they were unconsciously trying to resemble Rajneesh, instead, there was much easy talk of the difficulty of shaving in cold water and the poor quality of Indian razor blades. (For that matter, it did not require psychic gifts to see that many of the women are plainly in love with Rajneesh.)

They are, as I say, free of doubt; but they wear their certainty like a nimbus, not a sword. A Canadian girl I met had an ease and naturalness that were like magic; she made me want to hug her, though I hardly need say I didn’t. (Only afterwards did I realize that if I had done so she would have taken the gesture for no more than it was: an innocent salute to her almost incredible vitality).

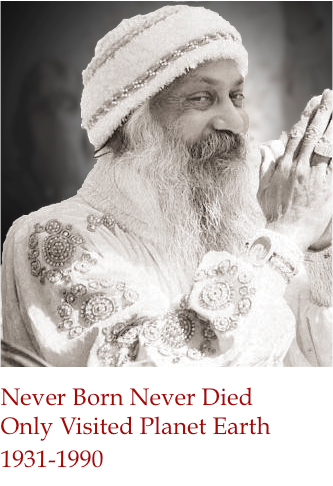

Even more relaxed was the formidable Laxmi, one of the only two people who ever see Rajneesh alone; she is the administrative head of the enterprise, and she glows with a force that nearly knocked me down. And she was the first to say, in answer to my question as to what Rajneesh was to them, that they regarded him as God. I invited her to elaborate, and she willingly did; but if he is God, he is a very undeified one, and certainly in his discourses there is no hint even of ”Who say ye that I am?”, only a powerful sense that he is a conduit along which the vital force of the universe flows. (One of the ashram-dwellers, when I asked the same question — what do you regard Rajneesh as? — put it impressively in two words: ”A reminder”).

But there is no doubt that Rajneesh is regarded, at the very least, of being possessed of psychic powers. He never now leaves his quarters, except for the morning discourses (the evening gatherings are held on a terrace abutting on to his rooms, and he has even given up his former practice of walking in his private garden) ; when I asked why he never looked in on the various groups to see how the work was going, the reply, immediate and without affectation, was, ”But he does – only not in the body”. He speaks for himself at the daily discourses, of course, and for the rest of the time Laxmi speaks for him.

On my second visit, however, last week, I could almost have wished she had not, for she told me of his view that Mahatma Gandhi was wrong, in his attempt to break the hideous grip of the caste system, to call the ”Untouchables” Haridjans, meaning ”Children of God”, for this had had the effect of boosting their ego — a remark which must rank high on anybody’s list of the dozen most ridiculous things ever said.

There is constant talk of a move to the new ashram, for which planning permission is still being laboriously negotiated. This is to be so large that all the sannyasin who want to live on it will be able to do so, and it will be entirely self-supporting; I was even shown detailed coloured drawings of the projected layout and buildings. On my first visit I sensed, or thought I did, that the whole project was chimerical, that the new ashram was to remain a dream, and that the dreaming was itself part of the technique, but on my second they insisted that the project was realistic and their intentions definite. I have heard the sannyasins’ temporary sojourn at the ashram (many come for a month or so at a time, often using their annual leave for the purpose) described as a holiday; if so, it is a holiday with remarkably therapeutic qualities, for I met no one who did not testify to the gains the experience had brought, and none who lacked the visible sign of such gains.

Is anything lost? I think not, but I am not quite certain. For some, perhaps, there is a softening of the wrong kind, a loss of definition, of individuality in the better sense. I found myself wondering how they would get on in extreme situations, of privation or persecution, or even flung back into the pressures of the life the rest of us lead. Perhaps some would be unable to cope (but then, look at the numbers who are unable to cope right now, without having had any transformative experience). Certainly they all feel secure — not in Rajneesh’s protection, but in their own new found wholeness.

Outside, too, there were reminders of a world elsewhere. In Poona I saw the reception after a Parsee wedding, opulent beyond imagining, set in a fairy-lit garden with Strauss waltzes amplified into the night, and a present-laden receiving line that stretched on for ever. I also saw the old man with a legless child, begging by the roadside, and the tents of sacking beneath the bridge near by. Inside the tents could be glimpsed neatness and order among the pitiful possessions, a people still unbroken by poverty. To Rajneesh’s followers, the wedding-guests and the tent-dwellers are suffering from the same spiritual wan, and so no doubt they are; but I think it will be some time before either group recognizes the fact.

At the evening darshan, Rajneesh initiated new sannyasin, discoursing beautifully and poetically to each on the theme of the new name he or she had acquired; he welcomed back, with a huge and radiant smile and apt words of greetings, those who had been away; he gave a third group an extraordinary ”energy-transfer”, pressing with his middle finger (like a violinist stopping a string) on the centre of their foreheads, over the ”third eye” to which experience reactions clearly varied from nothing at all to something close to convulsions; and he said an equally individual farewell to those who were leaving, ending in each case with the same formula, an inquiry as to their destination followed by the words ”Help my people there”.

Some would say they would do better to stay in Poona and help the tent-dwellers; some, more subtly, would argue that they should help the wedding-guests. Some, and on the whole I rather think I am one of them, would say that both arguments have missed the point of Rajneesh’s teaching, which is concerned to enable the individual to put himself right, since until that is done he can hardly hope to put others right.

I came away, impressed, moved, fascinated, by my experience of this man (or God, or conduit, or reminder) and the people (”be ordinary and you will become extraordinary”) around him. I came away, also, to a haunting fragment of time; beside the road leading to the ashram there was, in addition to the beggars, a pedlar selling simple wooden flutes. As I passed him for the last time he was playing a familiar tune: how he had learnt it, and what he believed it to be, I could not even begin to imagine. It was ”Polly Put The Kettle On”.